苏格拉底反诘法:什么叫“科研”?

The Socratic method (also known as method of elenchus, elenctic method Socratic irony, or Socratic debate) is a form of inquiry and debate between individuals with opposing view points based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and to illuminate ideas.

It is a dialectical method, often involving an oppositional discussion in which the defense of one point of view is pitted against the defense of another; one participant may lead another to contradict him in some way, strengthening the inquirer's own point.

The Two Phases of the ClassicSocratic Method:

The Deconstructive Phase

The Constructive Phase

Plato VS MENO:

PERSONS OF THE DIALOGUE: Meno, Socrates, A Slave of Meno (Boy), Anytus.

MENO:Can virtue be taught ?

SORATES:What is virtue ?

In Plato’s dialogue Meno,Socrates says:So now I do not know what virtue is; perhaps you knew before you contacted me, but now you are certainly like one who does not know.

Here, Socrates aims at the change of Meno's opinion, who was a firm believer in his own opinion and whose claim to knowledge Socrates had disproved.

Socratic Irony: "I know that I know nothing"is a well-known English saying which is a misleading or at least imprecise translation of Plato's account of the Socratic Cultivation of Critical Thinking.

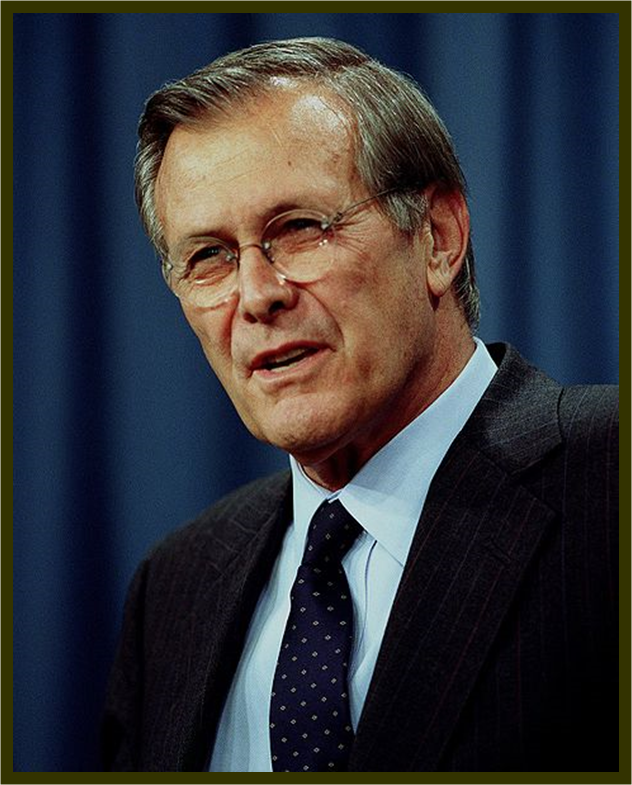

美国前国防部长拉姆斯菲尔德乃德裔美国人,1975年已被当时美国总统福特委任作国防部长,乃历届内阁最年轻的国防部长,当乔治·布什当选为美国第四十三任总统时,拉姆斯菲尔德被布什委任再出任国防部长一职,成为历届内阁中最年长的国防部长。

美国前国防部长拉姆斯菲尔德乃德裔美国人,1975年已被当时美国总统福特委任作国防部长,乃历届内阁最年轻的国防部长,当乔治·布什当选为美国第四十三任总统时,拉姆斯菲尔德被布什委任再出任国防部长一职,成为历届内阁中最年长的国防部长。

美国前国防部长的“苏格拉底之问”模仿版:

Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know.

We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns - the ones we don't know we don't know.

gadfly:雅典城的牛虻(害虫)

gadfly:雅典城的牛虻(害虫)

Socrates’ life as the “gadfly” of Athens began he questioned the men of Athens about their knowledge of good, beauty and virtue, but found that they knew nothing.

He concluded that he was wiser because he knew that he knew very little.

Convictions,when held too tightly, blind us in a way that traps us within our own opinions.Although this protects us from uncomfortable ambiguities and troublesome contradictions, it also makes us comfortable with stagnation and blocks the path to improved understanding.

In other words, without the capacity to question ourselves the possibility of real thinking ceases.