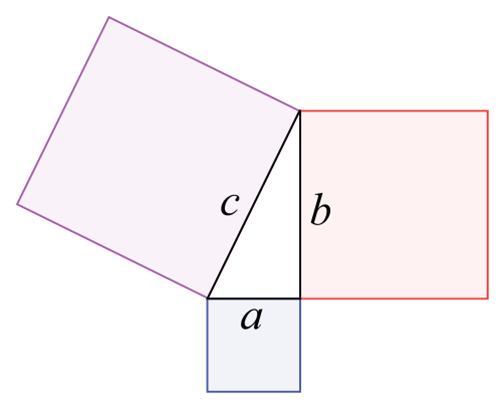

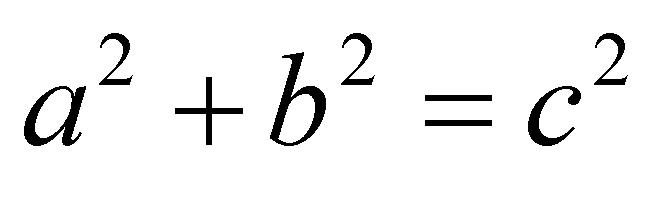

Pythagorean theorem In right-angled triangles,the square on the side subtending the right-angle is equal to the (sum of the)squares on the sides containing the right-angle.

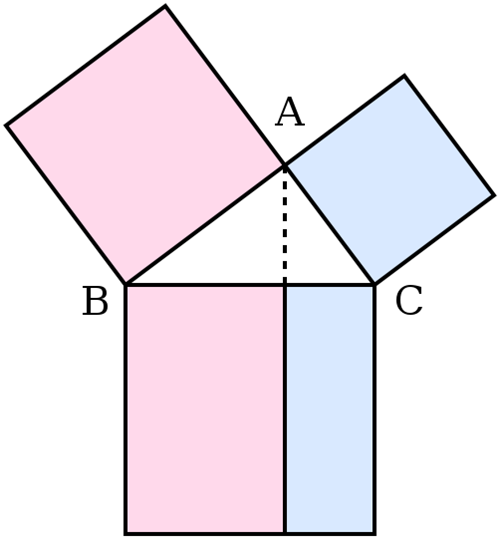

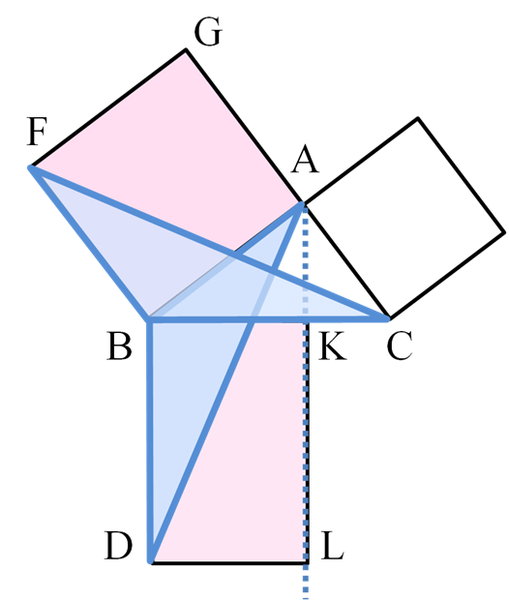

Proposition 47 in Book 1Euclid's proof.Let A, B, C be the vertices of a right triangle, with a right angle at A.

Drop a perpendicular from A to the side opposite the hypotenuse in the square on the hypotenuse.That line divides the square on the hypotenuse into two rectangles, each having the same area as one of the two squares on the legs.

For the formal proof,we require four elementary lemmata:

1.If two triangles have two sides of the one equal to two sides of the other, each to each, and the angles included by those sides equal, then the triangles are congruent (side-angle-side).

2. The area of a triangle is half the area of any parallelogram on the same base and having the same altitude.

3.The area of a rectangle is equal to the product of two adjacent sides.

4.The area of a square is equal to the product of two of its sides (follows from 3).

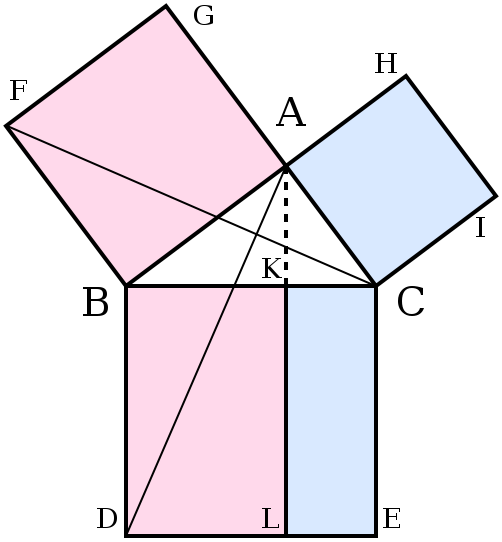

Next, each top square is related to a triangle congruent with another triangle related in turn to one of two rectangles making up the lower square.

The proof is as follows:

1.Let ACB be a right-angled triangle with right angle CAB.

2.On each of the sides BC,AB, and CA, squares are drawn, CBDE, BAGF, and ACIH, in that order. Theconstruction of squares requires the immediately preceding theorems in Euclid, and depends upon the parallel postulate.

3.From A, draw a line parallel to BD and CE.It will perpendicularly intersect BC and DE at K and L, respectively.

4.Join CF and AD, to form the triangles BCF and BDA.

5.Angles CAB and BAG are both right angles;therefore C, A, and G are collinear. Similarly for B,A, and H.Showing the two congruent triangles of half the area of rectangle BDLK and square BAGF.

6.Angles CBD and FBA are both right angles; therefore angle ABD equals angle FBC, since both are the sum of a right angle and angle ABC.

7.Since AB is equal to FB and BD is equal to BC,triangle ABD must be congruent to triangle FBC.

8.Since A-K-L is a straight line, parallel to BD, then parallelogram BDLK has twice the area of triangle ABD because they share the base BD and have the same altitude BK, i.e., a line normal to their common base, connecting the parallellines BD and AL.(lemma 2)

9.Since C is collinear with A and G, square BAGF must be twice in area to triangle FBC.

10.Therefore rectangle BDLK must have the same area as square BAGF =AB².

11.Similarly, it can be shown that rectangle CKLE must have the same area as square ACIH =AC².

12.Adding these two results, AB²+AC² = BD × BK + KL × KC.

13.Since BD = KL, BD × BK + KL × KC = BD(BK + KC) = BD × BC.

14.Therefore, AB²+AC² =BC²,since CBDE is a square.