The Renaissance (UK: /ri‵neisəns/, US: /‵rɛnisɑːns/, French : /ʁənɛsɑ̃ːs/,Italian: Rinascimento, from ri- "again" and nascere "birth") was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe.

文艺 literature and art:文学和艺术,有时指文学或表演艺术,是人们对生活的提炼,升华和表达。文艺的,开始意味着人类的文艺复兴,人类将重新发现了人和人格的伟大,肯定了人的价值和能力,提出人要养育人格……

Renaissance是一次导致西洋全面走向现代社会的改革开放与思想解放运动。 如果按照百年以来我国大众对“文艺”一词的认知,本课程教师认为我国使用百年的“文艺复兴”词语根本不足以反映Renaissance的本意。

Topics:

Architecture

Dance

Literature

Music

Painting

Philosophy

Science

Technology

Warfare

ルネサンス(仏: Renaissance 直訳すると「再生」)とは、一義的には、14世紀 - 16世紀にイタリアを中心に西欧で興った古典古代の文化を復興しようとする歴史的文化革命あるいは運動を指す。また、これらが興った時代(14世紀 - 16世紀)を指すこともある。

Historiography:The term was first used retrospectively by the Italian artist and critic Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) in his book.The Lives of the Artists (published 1550).However, it was not until the 19th century that the French word Renaissance achieved popularity in describing the cultural movement that began in the late-13th century. The Renaissance was first defined by French historian Jules Michelet (1798–1874), in his 1855 work, Histoire de France.

即便按照百年以来我国大众对“文艺”一词的认知,Renaissance仅仅包含如意大利三杰(达芬奇,米开朗基罗与拉斐尔)所代表的美术创新,也是与古希腊,与科学密不可分的。我们这里先不提人类历史上唯一的文理“通才”达芬奇,没有古希腊欧几里德几何学的重生,没有在欧几里德几何学的直接教导下成才的穆斯林学者的科学巨著对西欧人的指引,就没有这三杰。As a cultural movement, it encompassed a flowering of literature, science, art, religion, and politics, and a resurgence of learning based on classical sources, the development of linear perspective in painting, and gradual but widespread educational reform.

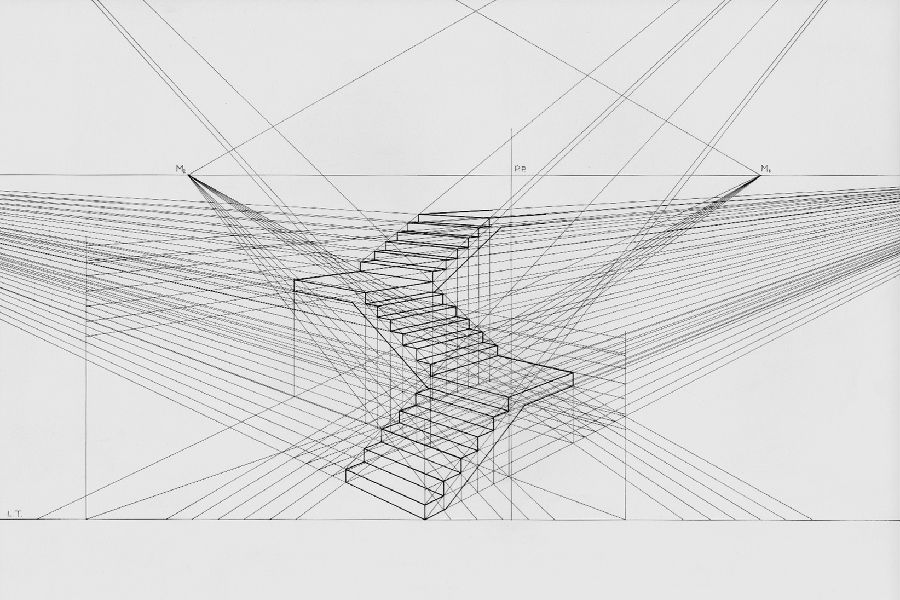

透视画法:Systematic attempts to evolvea system of perspective are usually considered to have begun around the 5th century B.C. in the art of Ancient Greece, as part of a developing interest in illusionism allied to theatrical scenery and detailed within Aristotle's Poetics as"skenographia": Using flat panels on a stage to give the illusion of depth.The philosophers Anaxagoras and Democritus worked out geometric theories of perspective for use with skenographia. Euclid's Optics introduced a mathematical theory of perspective;Prior to the Renaissance, Alhazen (in his Book of Optics in Latin as De aspectibus or Perspectiva, written in 1021), explained that light projects conically into the eye.Alhazen's geometrical, physical, physio-psychological optics resolved in this the ancient dispute between the mathematicians (Ptolemaic and Euclidean) and the physicists (Aristotelian) over the nature of vision and light.He also showed that vision is not merely a phenomenon of pure sensation (namely what results from the introduction of light rays into the eyes), but that it involves the faculties of judgment, imagination and memory.Alhazen's geometrical model of the cone of vision was theoretically sufficient to translate visible objects within a given setting into a painting, and this was also supported by his experimental affirmation of the visibility of spatial depth; hence of offering a proper ground for the idea of perspective. Moreover, Alhazen presented a geometrical conception of place as spatial extension (a postulated void), and he refuted the Aristotelian account of topos as a surface of containment.Alhazen's mathematical definition of place was more akin to Plato's notion of Chora as 'space', yet conceived on pure geometric grounds to facilitate the use of projections. In all of this, Alhazen was concerned with optics, with vision, light ……Conical translations are mathematically difficult, so a drawing constructed using them would be incredibly time consuming.

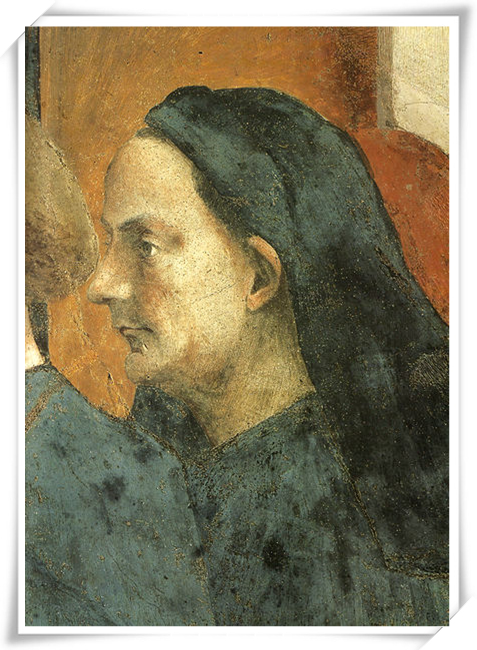

Brunelleschi

Brunelleschi

(1377-1446)

Architecture

Sculpture

Mechanical

engineering

透视画法

Brunelleschi was one of the for emost architects and engineers of the Italian Renaissance. He is perhaps most famous for inventing linear perspective and designing the dome of the Florence Cathedral.

emost architects and engineers of the Italian Renaissance. He is perhaps most famous for inventing linear perspective and designing the dome of the Florence Cathedral.

His accomplishments also included bronze artwork, architecture, mathematics, engineering (hydraulic machinery,clockwork mechanis,theatrical machinery, etc) and even ship design.

In about 1413, Brunelleschi demonstrated the geometrical method of perspective, used today by artists, by painting the outlines of various Florentine buildings onto amirror……

Rays of light travel from the object, through the picture plane, and to the viewer's eye. This is the basis for graphical perspective.

布鲁内莱斯基设计的佛罗伦萨圣母百花大教堂穹顶

布鲁内莱斯基设计的佛罗伦萨圣母百花大教堂穹顶

雕塑:

Ghiberti(1378—1455)

Ghiberti(1378—1455)

佛罗伦萨圣若望洗礼堂第一、二套青铜大门的作者,特别是第二套,它们更为自然,运用透视,也更为理想化。米开朗基罗称为这些场面为“天堂之门”。与前一位师兄弟在雕塑方案竞争中获胜。

By the 14th century, Alhazen's Book of Optics was available in Italian translation. Ghiberti relied heavily upon this work, quoting it "verbatim and atlength" while framing his account of art and its aesthetic imperatives……

Alhazen’s work was thus"central to the development of Ghiberti’s thought about art and visual aesthetics" and "may well have been central to the development of artificial perspective in early Renaissance Italian painting."

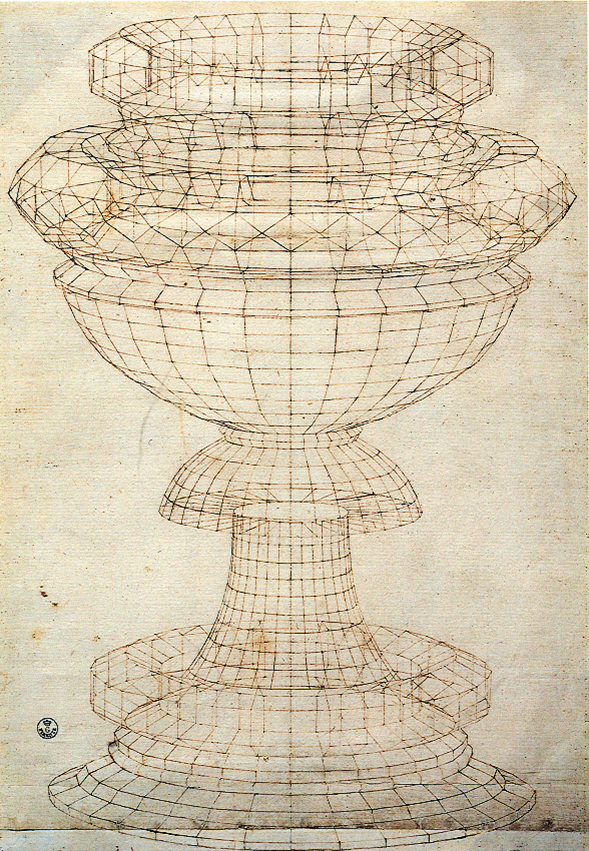

Perspective study of a vase By Paolo Uccello

(1397—1475)

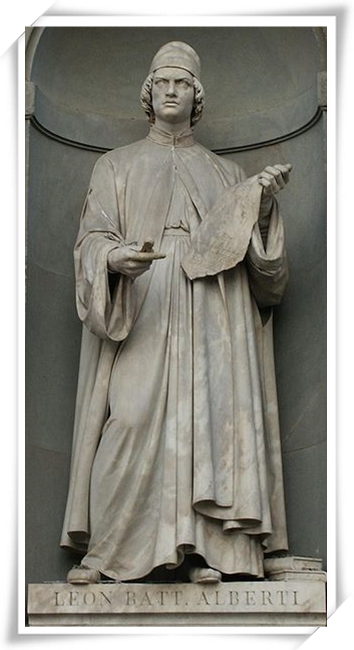

Leon Battista Alberti阿尔伯蒂

Leon Battista Alberti阿尔伯蒂

(1397—1475)

Priest Polymath

阿尔伯蒂是佛罗伦斯一个富裕的商人与博洛尼亚的一位寡妇在热那亚所生的两位私生子之一。由于他的私生子身份,他的一家被统治佛罗伦斯的阿尔伯蒂家族禁止在佛罗伦斯居住,而另一方面,他的母亲亦于瘟疫中死去,所以莱昂在早年与父亲只好投靠在威尼斯办银行的叔叔。在1428年时,家族的禁令撤销,使他们一家可以回到佛罗伦斯定居。

阿尔伯蒂是意大利文艺复兴时期的建筑师、建筑理论家、作家、诗人、哲学家、密码学家,是当时的一位通才。阿尔伯蒂著有“大艺术”三部曲:《论绘画》、《论雕塑》与《论建筑》,这三部曲在意大利文艺复兴时期广为流传。

他在《论建筑》这本书里面体现了从文艺复兴人文主义者地角度讨论了建筑的可能性,并提出应该根据欧几里得的数学原理,在圆形、方形等基本集合体制上进行合乎比例的重新组合,以找到建筑中“美的黄金分割”。

他在《论绘画》开篇时写道: "To make clear my exposition in writing this brief commentary on painting, I will take first from the mathematicians those things with which my subject is concerned."This treatise (Della pittura)was also known in Latin as De Pictura, and it relied in its scientific content on classical optics in determining perspective as a geometric instrument of artistic and architectural representation.Alberti was well-versed in the sciences of his age. His knowledge of optics was connected to the handed-downlong-standing tradition of the Arabic polymath Alhazen,which was mediated by Franciscan optical workshops of the13th-century Perspectivae traditions of scholars such as Roger Bacon (similar influences are also traceable in the third commentary of Lorenzo Ghiberti).In both Della pittura and De statua, a short treatise on sculpture, Alberti stressed that "all steps of learning should be sought from nature." The ultimate aim of an artist is to imitate nature.